Contents

Japanese food " Unagi "

Even today, many of the habits of eels remain mysterious, as do the origins of the Japanese fondness for eating them, although it is thought the custom originated in the Nara period. They even appear in the Manyoshu – written with different kanji from that in use today. Many other old literary references have them as “munagi” in contrast to the modern “unagi,” and we can also find early traces of “unagi” dishes, but eel only caught on widely in the Edo period, when they were valued as an aid to avoiding summer heat exhaustion, and also as a delicacy to go with drinks, being rich in nutrients, especially protein, as well as flavor, and possessing a robust life force that kept them alive even after being caught as long as their skin was wetted. Eels have a unique shape; so too did tools for preparing these slippery, hard-to-grab creatures evolve into unique shapes and win names like “eyeletter” and “eel knife.” The eel knife in particular is capable of doing all the necessary tasks to dress an eel for cooking: eye-stabbing, gutting, bone-cutting, skinning, and so forth. A multi-talented star!

Usually, in the Kansai region, eel are split open down the back, whereas in Kanto they are split open down the stomach, but in Tokyo, traditionally a martial city, unwonted associations with hara-kiri caused chefs to shy away from the stomach-splitting method, with the result that eel are split open down the back here, too, in the middle of Kanto. Conversely, in Osaka, the largest city in the Kansai region, it is said that the expression “spill one’s guts” led to the adoption of the stomach-splitting method. Other slight regional differences in preparation exist: for instance in Kansai eel are dressed and skewered, then roasted, but Tokyo chefs add an extra step of steaming them. Which method is better is of course a matter of personal preference, and in the end, I believe the skills and philosophy of each individual chef affect the taste more than any difference in cooking method.

For instance, just as in the case of yakitori restaurants, it is often said that the tare (sauce) is the real deciding factor in the quality of an eel restaurant. The tare, in a sense, is the body of the taste, the restaurant’s “secret recipe.” Yet this is not a recipe that can be made in one day. It is the depth, the fullness, the essence of that restaurant’s history, built up over years, passed from one master chef to the next. It is the trick that home chefs cannot hope to imitate. Even if by repetition, like disciples of a master swordsmith forging blade after blade, we could master the dressing, the skewering, the steaming of eel, we would be helpless to conjure up the tare. Even if we used the restaurant’s recipe, we could not produce the same taste. This is because restaurant tare has absorbed the umami, or savor, of all the thousands of eels that have been submerged in it. Therefore, there may be some truth in the story that if there was a fire, the first thing a master chef would save from the flames would be the pot containing his tare. Naturally, the tare dwindles with use, so it is periodically replenished. It is, I suppose, illogical to think that we may literally be savoring decades-old tare, but there is still a certain romance in the idea.

In the west of Tokyo, at Ogikubo, the fourth station from Shinjuku on the Chuo line, stands the long-established eel restaurant Azumaya. One afternoon recently I had the honor of observing the process that eventually lands the eel in the “unagiju” lacquered box in which it is borne to table. Before my eyes, the master chef unfurled his techniques with dispassionate flair, not a single movement wasted, and as the process continued a rich perfume began to waft through the air. The fragrant smoke! The sound of sizzling, heightening expectations! The gentle, dignified light of charcoal embers… the occasional passage of a refreshing breeze. Shutting my eyes and taking a deep breath, I was able to imagine myself on a bustling, prosperous Edo city street.

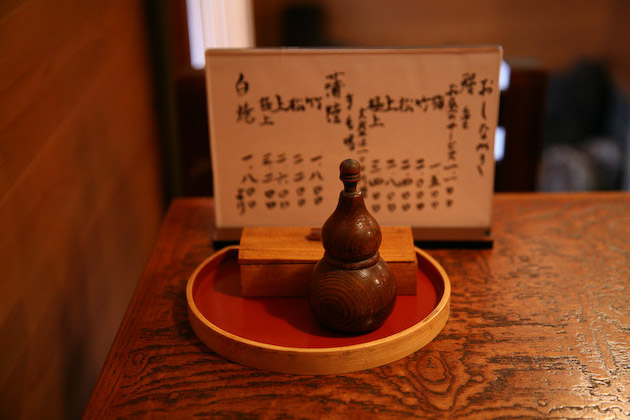

Arriving a few minutes late for my appointment, I was greeted by the smiling couple who run Azumaya. The restaurant is not large, but its interior has a calm and relaxed atmosphere. Autographs and pictures drawn by regular customers are stuck casually up on the walls, near some flowers marvelously arranged by the master chef’s wife’s own hands. I followed them into the kitchen to watch them work. In the preparation area on the left of the entrance, a massive chopping board was placed, and in front of it a stack of black baskets, probably about sixty centimeters in diameter, held a number of lively, wriggling eels.

“Very well, let’s get started.” So saying, the master chef drew a splendid eel out of the basket, settled its head on its right side, and drove his eyeletter into its eye, pinioning it. Faster than the eye could follow, he inserted his knife and began to dismember it. His consummate flair made it look easy, but I could see at a glance that it was the flair born of an art which has been forged by long years of experience. Bang! There was something ineffably beautiful about the way he slapped his knife down on the chopping board. Swiftly inserting his knife, needing no more than one or two movements for each task, in a blink he had sliced the eel into 20-centimeter oblongs. Of course, its giblets would be variously roasted and used for eel liver soup, so he would not have dreamed of throwing them away.

Next he skewered the eel. Breadthwise, from the near side to the far side he drove the skewer into the oblong pieces、impaling two at a tim. This, too, is a task that would be fumbled by an amateur – the skewer would not go in properly, or it would pierce the eel messily – but the master chef thrust the implement home as if it were the most natural movement in the world.

Then to the roasting. He stoked the fire and fanned it up with an uchiwa fan. Accurately judging the proper moment, he balanced the skewered eel on two metal support sticks above the charcoal stove’s burner, the sticks being slightly shorter than the length of the skewer. Immediately a sizzling sound arose and smoke wafted forth. Many restaurants nowadays use electric burners for convenience, but the master chef of Azumaya still uses charcoal, as if that were perfectly natural. The heat of the charcoal embers, which can reach 1000 degrees Celsius, gives the eel a clement yet certain roasting, while excess fat drips off into the coals. That heat, together with the smoke that rose from the stove, soon filled the whole kitchen. “In summer, I change my shirt I don’t know how many times a day, and I have to be sure to get enough liquids,” the master chef told me gently, without pausing in his task for a moment. With his uchiwa fan, he directed fresh air over the charcoal, and while checking constantly on the progress of the roasting eels, he turned them over and over again. These tasks he repeated again and again. I too was lightly perspiring, though it was a cool spring day. What must it be like in this kitchen on a hot summer day? “New fans wear out and break straight away,” the chef commented, plying the uchiwa fan he had reinforced himself by hand. Flap, flap, and little by little the eels were roasting. Before I knew it they had turned white and their skins were lightly charred. They were now what is known as “white roast eel.”

Next, the steaming. With a light touch, the master chef placed the roasted eel in a steamer pot that had been placed in readiness beside the burner. If the roasting had been a difficult task, it seemed like child’s play next to judging the length of time the eel should steam, which varies with the season, with the temperature, with the condition of the eels themselves. This above all is a professional technique. Today, the steaming took about ten minutes. The master chef removed the eel from the steamer pot and prepared to return them to the burner for another roasting. But this time it was to be different: this time they were to be roasted with Tare. Deliberately, the master chef lowered each skewer into the tare pot until the eel pieces were entirely submerged, the liquid almost touching his fingers. Then, back above the charcoal fire they went. Shu… they crackled, as all around the stove instantly spread a deeply familiar, sweet and fragrant smell. Flipping the eels, the chef immersed them again and again in the tare, again and again returning them to the stove, until finally they were done, and his wife heaped rice in the unaju box, and onto this too the chef evenly poured tare from a toothed ladle he had made by hand, and then he removed the skewers and laid the eel pieces on the rice and the dish was complete. A marvelously efficient husband-and-wife combination!

Eel dishes are usually served with oshinko pickles, which have also been an important feature of eel restaurants’ menus from time out of mind. (The oshinko at Azumaya are also an absolute must!)

After my research was complete, the master chef and his wife served me a full-course meal including roast giblets and eel liver soup. (And even beer!)

The eel was so tender that my chopsticks almost speared straight through it as I carried a piece, together with a mouthful of rice, to my lips.

!!!

A joy that left me speechless spread from the top of my tongue throughout my body. The exquisitely roasted eel, neither too sweet nor too spicy; the perfectly rich tare; the fluffy white rice… The moment the first mouthful crossed my lips, a symphony of inexpressible umami, sweetness, and fragrance suffused my entire palate. Then, as it slid down my throat, happiness and contentment spread throughout my whole body. It was an instant of supreme bliss. I munched on the pickles, drank my beer, and talked with the master chef and his wife about this, that, and the other. The spring afternoon passed slowly, leaving a deep impression on my heart.

To receive food is to receive life. No matter how unrecognizable ingredients in a dish may be, that they were once living is certain. We receive life in various shapes, not only from animals but from fish, birds, vegetables, and fungi such as mushrooms. Could this be the destiny of every living thing? In any case what is crucial is to acknowledge this fact and not to forget to be thankful. In this Age of Satiety, when we are urged to consume as if it were a way of earning spiritual merit, in this epoch when bigger things and newer things are seen as better by definition, the words of the master chef of Azumaya, “I’m only doing the obvious thing in the obvious way,” while expressing modesty, resonate strongly in the heart as sternly passionate. “To do the obvious thing in the obvious way” – this is far from easy. As only those who make it their stance to “do the obvious thing in the obvious way” can know, in a sense, it may mean a long and winding road. But I am not just imagining that when we meet people with such hearts, people with simple gazes, our own hearts are emboldened. That is where I am right now: I cannot help thinking, “I want to live simply.”

Azumaya is 7 minutes on foot from the Ogikubo JR and subway station. Go out of the north exit, cross the bus rotary, and walk to your right along Ome-Kaido (towards Shinjuku) for about 150 meters. Go into the alley on your left, walk 30 meters, then turn right. Keep walking for another 150 meters, and on your right you will find Azumaya, where you may sample the taste that the master chef has been perfecting for the last 47 years.

Azumaya

Open: 11:30am to 14:00pm, 17:00pm to 20:00pm

Closed: Tuesday

2-3-13 Amanuma Suginami-ku, Tokyo Japan

03-3392-5232